On This Page

- Scope

- Searching

- Browsing

- “Original” and “Normalized” Results

- Reading an Entry

- Navigating the Lists of Results

- Known DEx Issues

- Find an error?

DEx offers insight into the reception history of early modern drama by giving people access to evidence about what early readers and playgoers took, literally and figuratively, from plays. Early readers and playgoers would copy selections from plays into their manuscripts (often commonplace book or miscellanies); DEx is a record of what people copied.

You can navigate DEx: a Database of Dramatic Extracts by search or browse. Learn more about the manuscripts in our database on the “about the manuscripts” page.Scope

DEx includes manuscript extracts, that is, selections people copied by hand. Printed sources, including commonplace books, also included selections from early modern plays.

DEx includes early modern English plays that were first written between 1642 and copied into manuscripts until around 1700.

We are still actively adding materials to DEx, and we know there will be more to be added! If you know of an extract that isn’t yet in our database, let us know.

You can see a list of all the primary sources included in DEx in the database when you choose to view the results by manuscript: each manuscript name is clickable and will bring you to all of the dramatic extracts from that manuscript.DEx offers transcriptions of dramatic extracts and marginalia or notes that surround those extracts. The other items in a manuscript (receipts, non-dramatic poetry, aphorisms, etc) are not transcribed. We link to other online resources where available so that you can get a fuller understanding of each manuscript.

Searching

Your search results will bring up the search term no matter what field it appears in: so, for instance, a search for “Antonio” will bring up results where Bassanio says Antonio’s name in Merchant of Venice; all extracts from Antonio and Mellida; as well as all extracts spoken by characters named Antonio–of which there are quite a few. There is no fuzzy searching in DEx, however, so a search for “Antonio” will not bring up characters with similar names such as Antony (in Julius Caesar), Antonius (in The Tragedy of Nero), and Anthonio (in The Maid of Honour), to name only a few.

Searches are not case sensitive.

You can use a number of Boolean search operators to refine your search.

- The * (asterisk) functions as a truncation marker. A search for [lov*] will find love, loved, loves, loving, and so forth.

- The ? (question mark) is a wildcard operator, which replaces just one letter. A search for [practi?e] will return results with both practice and practise.

- “” (quotation marks) offers phrase searching functionality, which means the words must appear in the order they are searched. So a search for [love honour] without quotation marks will bring up every extract that has both the words love and honour, whereas a search for [“love honour”] with quotation marks will bring up all extracts that say “love honour” in that order

- Typing NOT in uppercase characters means that the second word will be removed from the search results. Searching [queen NOT king] will bring up every extract with the word queen that does not contain the word king.

- The default search uses a Boolean AND operator. This means that typing two words into the search bar will bring up any extract that has both of those words. If you type two words and get no results, we suggest searching each individually.

Browsing

You can browse the extracts in a few ways:

When you choose any of these options, the default result will be the first alphabetical listing–so, perhaps ironically, the first result for “playwright” lists all of the “anonymous” works.

You can choose to change between any of these navigation options from the top menu in the database.When you see your results from search or browse, they will be “original” spelling. This is the spelling in the manuscript. You can toggle the spelling at the menu at the top. “Normalized” spelling is a modern-spelling version of the results (see below for more details).

At the top of any search or browse result, you will see the number of extracts listed in that category.

“Original” and “Normalized” Results

You can toggle between “original” and “normalized” results using the top menu of the database.

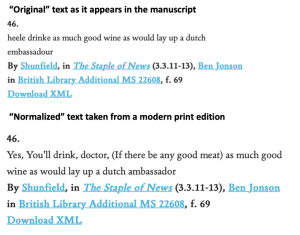

The “original” version of an extract is a transcription of the original manuscript.

For the purpose of this project, we have decided that punctuation, capitalization, and lineation are accidental in the sense that they vary so much we have not accounted for them in the transcriptions. Likewise, u/v and i/j can be difficult to determine in some early modern hands, so we have erred on the side of normalizing these entries.

We have, when possible, captured manuscript abbreviations as they appear using the Medieval Unicode Font Initiative, which can sometimes lead to odd textual displays. Abbreviations are expanded in “normalized” results.

The “normalized” version of an extract is the version as it appears in an edited modern-spelling version of the text (where available). This is also where the line numbers for the extracts are taken. To learn about how modern versions are selected, see “About the Bibliography“; you can also see the complete list of early modern playtexts we compared to the manuscript sources. Including normalized texts also accounts for variations in early modern spelling. When we not have an edition with modern spelling available, we normalize the spelling ourselves to facilitate search.

“Normalized” versions are, of course, not a record of a compiler’s source: firstly, some people copied extracts while they were in the theatre watching plays; secondly, some people were copying from now-lost print or manuscript texts; thirdly, in many cases it is not possible to ascertain the specific source text. Manuscript compilers often changed the texts they copied, sometimes quite extensively. The “normalized” text in DEx is not intended to suggest that this was the text the copyist used: rather, it is designed to make it possible to search the extracts without knowing how a copyist might have changed a text. This makes it possible to find passages from a play even if they have been altered, even if a copyist has omitted a brief phrase.

Take, for instance, the following example from Ben Jonson’s The Staple of News, where the compiler has rephrased a passage.

If you would like to visually collate differences between original and normalized versions of extracts in order to see how widely an extract differs from an early printed source (which, of course, might not be the source that copyist consulted), we recommend using Juxta or another online collation software. You can use Juxta with either the results as they appear in the database or the original TEI-XML files, which are available to download for each manuscript. To compare smaller pieces of text, you can use the search function to find a given extract then toggle between results.

Reading an Entry

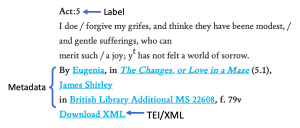

Taking the above example from the Staple of News, here are the key parts of an entry:

- Label: if a compiler has added something to the extract such as a marginal label, we include this in bold text. We do not place labels in their position on the manuscript page, though sometimes, when labels are in-line with the text, they are indicated as such. Some labels are as simple as commonplace markers (“) or numbers.

- Metadata: metadata fields in blue (character, title, playwright, and manuscript) are all clickable. Clicking on one will take you to all other extracts in DEx with the same metadata field (for instance, all extracts by the same character; all extracts from the same manuscript)

- Additional metadata includes line numbers, where possible, from the plays. These are taken from modern editions. For Shakespeare, for instance, we use Internet Shakespeare Editions texts, which uses TLN (through-line numbering); for many other plays, we use traditional act.scene.line numbers (x.y.z); where line numbers are not available, we offer simply act.scene information (x.y); and in rare cases, where there is no known modern edition, we will simply have consulted the first known printed edition and give signature numbers. To see where the line numbers are taken, consult our

- Additional metadata also includes folio numbers for the manuscript. Note that some manuscripts have page numbers instead of folios; these will be marked with “p.” instead of “f.”

- TEI/XML: when you “search” you will see a “Download XML” button with each extract, which will download the XML of the entire manuscript. When you are browsing, you can access the TEI/XML by clicking on the manuscript title and choosing “Download XML” from the list of results.

Some notes on the above extract:

- the punctuation–in this case, virgules/slashes–is from the original manuscript

- spelling, including scribal abbreviation, is retained

Navigating the List of Results

When results are returned from a given manuscript, they appear in same order as in the manuscript.

If you are looking for a particular word or phrase on a large page of results, we recommend using your computer’s “find” function (cmd-F on a Mac; ctrl-F on a PC). This will also show you the number of times a given word or phrase appears on a page of results.

Known DEx issues

There are currently the following known problems with DEx:

- When there is more than one speaker for a given passage (that is, something spoken chorally), only the first speaker appears as the “character” for the extract

- Some labels are manuscript headings that apply to multiple extracts. We have chosen to include these only on the first extract because it clutters complicated search results even further. We are considering alternative display methods.

We look forward to addressing these when time and funding make it possible.

Find an Error?

If you have found an error on our site, we would love to hear from you. We also love to hear about new extracts to be included.

DEx has been the work of thousands of hours of collaboration, including with students who have learned paleography and text encoding. Likewise, technical updates can sometimes cause errors. We appreciate any feedback.